I struggle to find a good, or appropriate, balance between action and pontification—both are critically necessary elements for demonstrating success. As a new and nontypical face in the venture capital space it is even more critical to demonstrate a resounding understanding of facets of the business so that others feel a sense of safety/comfort in your presence and understanding of a sector that isn’t all that complicated—on the surface. However, the internal nuisances of venture capital are secondary to the braggadocious, and necessary, moments by which it is encapsulated. If you’re not telling your own story who will?

In venture we must present who we know, not what we know, in an effort to affirm a particular sense of place belonging—the closer you are to success the more successful you are perceived to be.

I am challenged by this system because I am not someone who has found the right internal balance of understanding that allows me to leverage a relationship over talent without considering all the possible talent that may exist sans relationship—a ramification of the disenfranchised.

As a queer Black person, I am not part of the archetype of venture capitalist before me—cis, white, male, non-queer, affluent/affluent adjacent, ivy/ivy adjacent. I am a cis-male, but then the archetype turns a sharp corner. I am a first-generation American immigrant from Jamaica West, Indies. I was a first-generation college student whose mother earned her GED. Yes, I may have my MBA, but I don’t come from a top pedigree school of business—I worked fulltime while earning my degree. I didn’t come to the venture space after having some big exit or after leaving a recently acquired start-up where I was employee number seven. I’ve been thoughtful and intentional about my actions and the relationships I’ve worked to foster and nurture—I truly do love people, humanity.

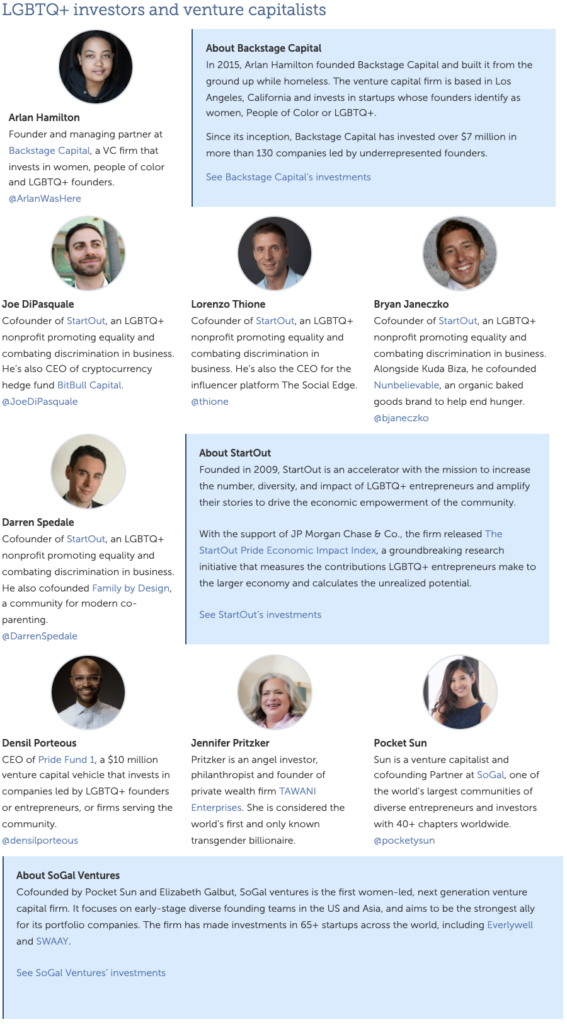

As a queer Black person, I am not part of the archetype of venture capitalist before me. There are not many queer venture capitalists and there are not many queer venture capitalists who are lauded among a group of heterosexual others. LGBTQI+ identities have now become slightly more common place in positions of leadership outside of traditionally queer spaces and are shaping and guiding industry—we are not part of the archetypical venture capital character and therefore not part of the archetypical venture investment strategy. Lorenzo Thione. Arlan Hamilton. Angel—Jennifer “Jenny” Pritzker. We each have had different paths to this place from where we are working to make more space for identities like us who have always been a part of creating profitable sectors across industries.

Serving as CEO of an early-stage venture fund is something akin to forecaster-guru-and-statistician in amalgamation. The ability to turn a phrase while ensuring you’re giving an accurate representation of your vertical, ventures, and valuations doesn’t only take knowledge and finesse, it takes time and repetition, and to truly be successful it takes access and trust. Thione, Hamilton, and Pritzker are some of the few who have pushed harder to realize a dream bigger than they the spaces in which we once singularly were allowed inhabit. We can be the inspiration for another archetype—one a little more inclusionary and frankly far more profitable.